The partnership involving the Scottish baronage and the top was usually fraught with strain, as barons sought to protect their liberties whilst the monarchy attempted to centralize authority. Through the old period, Scottish kings relied on the baronage for military support, especially throughout situations with Britain, but also sought to control their independence. The Conflicts of Scottish Liberty in the 13th and 14th generations highlighted the critical role of the baronage in national security, as barons like William Wallace and Robert the Bruce emerged as leaders of the opposition against English domination. But, the crown's dependence on the baronage also meant that edgy barons could present an important risk to regal authority. The 15th and 16th centuries found repeated struggles between the monarchy and overmighty barons, culminating in conflicts such as the Douglas rebellions, wherever strong baronial individuals challenged the crown's supremacy. John IV and his successors sought to weaken the baronage by marketing the power of the elegant courts and increasing the reach of main government, but the barons retained significantly of their regional power. The Reformation more complex this dynamic, as spiritual sections often aligned with baronial factions, resulting in additional instability. Despite these difficulties, the baronage kept an essential element of Scottish governance, their loyalty or resistance often determining the success or disappointment of regal policies.

The drop of the Scottish baronage began in the late 16th and early 17th generations, while the crown's efforts to centralize power and the adjusting character of land tenure evaporated their old-fashioned powers. The Union of the Caps in 1603, which brought John VI of Scotland to the English throne, marked a turning point, because the king's concentration moved southward and Scottish institutions were increasingly subordinated to British models. The abolition of genealogical jurisdictions in 1747, following the Jacobite uprisings, worked one last hit to the baronage's appropriate authority, stripping barons of the judicial forces and developing Scotland more completely in to the British state. However, the legacy of the baronage endured in Scotland's cultural and cultural memory, with several individuals maintaining their brands and estates whilst their political effect waned. Nowadays, the name of baron in Scotland is largely ceremonial, although it remains to carry historical prestige. The baronage's effect on Scottish record is undeniable, since it shaped the nation's feudal framework, inspired their legitimate traditions, and played a critical role in their problems for freedom and identity. The history of the Scottish baronage is therefore a testament to the complicated interplay of regional and national energy, highlighting the broader tensions between autonomy and centralization which have indicated Scotland's old development.

The financial foundations of the Scottish baronage were grounded in the land, with agriculture creating the cornerstone of the wealth and influence. Barons produced their money from rents, feudal dues, and the make of these estates, which were labored by tenant farmers and peasants. The productivity of these places different generally, based on factors such as for example soil quality, climate, and the baron's management practices. In the fertile Lowlands, baronies usually developed significant earnings, supporting extravagant lifestyles and permitting barons to buy military gear or political patronage. In the Highlands, where the ground was less amenable to large-scale agriculture, barons counted more heavily on pastoralism and the extraction of organic assets, such as timber and minerals. The economic energy of the baronage was ergo tightly linked with the output of these estates, and many barons took a dynamic role in improving their places, introducing new farming practices or growing their holdings through relationship or purchase. Deal also played a role in the baronial economy, specially in coastal parts where barons could benefit from fishing, delivery, or the move of wool and other goods. However, the baronage's economic dominance started initially to wane in the first modern time, as industrial agriculture and the increase of a money-based economy undermined conventional feudal relationships. The box movement and the Baronage toward lamb farming in the 18th century more disrupted the old get, displacing tenants and lowering the barons' get a handle on on the rural population.

The ethnic and architectural history of the Scottish baronage is evident in the numerous mansions, system houses, and manor houses that dot the Scottish landscape. These structures offered as equally defensive strongholds and representations of baronial power, highlighting the wealth and status of these owners. Many barons used seriously in their residences, constructing imposing rock systems or growing current fortifications to tolerate sieges. The look of those houses frequently incorporated equally realistic and symbolic things, with functions such as for example battlements, gatehouses, and heraldic designs focusing the baron's power and lineage. Beyond their military function, baronial residences were stores of social and political life, hosting events, feasts, and meetings that reinforced the baron's position as a nearby leader. The cultural patronage of the baronage also prolonged to the arts, with some barons commissioning operates of literature, audio, or visible art to celebrate their family's record or promote their political ambitions. The drop of the baronage in the 18th and 19th generations generated the abandonment or repurposing of many of these structures, although some remain as historical landmarks or individual homes. Nowadays, these buildings serve as concrete pointers of the baronage's once-central position in Scottish society, offering ideas into the lifestyles and aspirations of the powerful class.

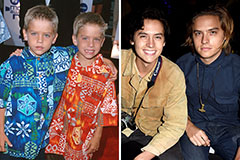

Dylan and Cole Sprouse Then & Now!

Dylan and Cole Sprouse Then & Now! Mason Gamble Then & Now!

Mason Gamble Then & Now! Barry Watson Then & Now!

Barry Watson Then & Now! Dawn Wells Then & Now!

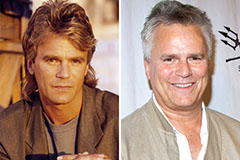

Dawn Wells Then & Now! Richard Dean Anderson Then & Now!

Richard Dean Anderson Then & Now!